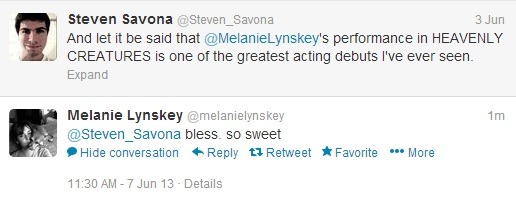

JUNE 3

Heavenly Creatures (Peter Jackson, 1994) = 4/5

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it's pre-Lord of the Rings Peter Jackson! Heavenly Creatures is an evocative tale of obsessive adolescent fantasy. It is darkly comical, whimsical, but most of all terrifying. There's something very disturbing about innocent escapism that evolves into the sinister. Kate Winslet is very good, but it is Melanie Lynskey in her debut role who impressed me the most. I let her know it and she responded, which may have made my year.

JUNE 4

The Intouchables (Olivier Nakache & Eric Toledano, 2011) = 4/5

It is far from the most original or intelligent film I have ever seen, but it was extremely hard not to like this one. Simply put, it is hilarious and heartwarming. It's a breath of fresh air for the buddy comedy genre. Cluzet and Sy are brilliant. I just feel as though there was a lot of untapped potential here. The direction is somewhat methodical (slick but feels too plotted) and the film could have been even greater in more experienced hands. Oh well, I shouldn't expect too much from a blatant crowdpleaser.

JUNE 7

Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977) = 3.5/5

This vibrant nightmare, while somewhat dated, offers a nice blend of cheese and scares. It's an important slasher film that I should have seen years ago. Some of the colours in this film are just out of this world, and the score by progressive rock band Goblin is the film's pulse.

JUNE 8

The Black Balloon (Elissa Down, 2008) = 4.5/5

I was really surprised by how much I loved this film. Thomas (Rhys Wakefield) develops a crush on Jackie (Gemma Ward), but any attempts to capitalise on those feelings are thwarted by Thomas' autistic brother, Charlie (Luke Ford). As you can imagine, a film with such a plot allows for plenty of emotional tension, and this is what makes the film so absorbing. I think it says a lot about the innate strength of family ties and the value of tolerance. There are no easy roles in this film, and everyone handles their part with aplomb. The cinematography is rather striking—we see Sydney in all its suburban splendour.

JUNE 9

City of God (Fernando Meirelles & Kátia Lund, 2002) = 3/5

Knowing this film is often hailed as one of the greatest of all time, there was a lot of pressure for me to like it. Unfortunately, it just didn't interest me a whole lot. Too many characters. Too much movement. All acceleration and no braking. I wanted to like it but it's sensory carnage. This film has been called the Brazilian Goodfellas, but I think Scorsese's film is streets ahead of this.

JUNE 10

Dogtooth (Giorgos Lanthimos, 2009) = 4/5

Three teenagers are confined to a property to endure a twisted form of home-schooling. They have no idea what life is like beyond the walls of the estate. It's not the easiest or most logical film to watch, but it is endlessly compelling. A daring work about power and indoctrination that is unashamedly nasty when it wants to be. It contains one of the most subtly evil film insults of all time: "I wish your children get all the wrong stimuli and grow to be bad." Imagine Haneke meets Von Trier meets Korine.

JUNE 11

The Red Shoes (Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, 1948) = 4.5/5

I had seen two other Michael Powell films before watching this and loved both: They're a Weird Mob and Peeping Tom. This was the first time I'd seen a Powell-Pressburger collaboration. The Red Shoes is a gorgeous film that captures the fervour of artistic impulse and the dizzying intoxication of the impassioned soul. It has aged magnificently, and Black Swan has nothing on it, in my opinion.

JUNE 12

The Loved Ones (Sean Byrne, 2009) = 1.5/5

As someone who is tired of seeing the same themes and tropes recycled in Australian cinema, The Loved Ones loomed as something refreshing. However, this desire to break free from the conventions of Australian cinema is what ultimately sullies the film. I can't remember the last time I saw a film that was so desperate for the validation of its audience. It seemed to be crying, "LOOK HOW SUBVERSIVE I AM!" The atmosphere just never feels right. The film is too aware of its grotesqueness and there is no nuance to anything. I also had no reason to empathise with the Xavier Samuel character. We just don't get to know him enough before he is seized by the sadistic Lola (Robin McLeavy). I suggest you do not show this film to your loved ones. They will disown you.

JUNE 13

The Piano Teacher (Michael Haneke, 2001) = 4/5

Don't go into this expecting a saucy teacher-student fantasy. Haneke strips sex of its intimacy, depicting it as a series of cold power plays. It's a meditation on expectation versus reality, and how we fall in love with the idea of a person. The film is slow and I found myself getting restless at times, but the characters are so multi-faceted that I couldn't help but be entranced. Isabelle Huppert is phenomenal in the title role.

JUNE 14

Bug (William Friedkin, 2006) = 3.5/5

I hated this film when I first saw it in my early teen years, but I'm SO glad I rewatched it! It's about fear and delusion. A poisonous folie à deux plays out in this flawed though frightening film. The performances from Michael Shannon and Ashley Judd are two of the most convincing I have seen in any film. I would have liked it even more if the execution was less stagy. I realise the film is based on a play, but this shows too much.

JUNE 15

Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley, 2013) = 4/5

There's a George Bernard Shaw quote: "If you can't get rid of the skeleton in your closet, you'd best teach it to dance." In Stories We Tell, Sarah Polley exhumes those skeletons from her family's closet, and they dance in the most beautiful way. Alternatively, her family secrets are not so much skeletons but embalmed corpses—you don't want them in your presence, but there's a twisted beauty about them. The film is a cathartic work that taps into the innately human desire to divulge; to tell stories. There's a point in the film where Polley mulls over her aspirations for the film. There was a point where Stories We Tell was just a story, and Polley didn't know whether to make a documentary for public release, a home movie, or an art project. I am glad she went with a documentary because it turned out very well, but any format would have reflected that human need to document. When extraordinary things happen to us, it is only natural to want to tell someone. In some cases it may be egotistical, but it's mostly a matter of captivating your audience with wide-eyed wonder. My full review can be read here.

JUNE 16

Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966) = 3/5

There's a lot to like stylistically, but there are too many meaningless sequences and I couldn't connect to it emotionally. Perhaps I would have enjoyed it more if I were more familiar with 1960s British culture, but this just came off as pretentious to me.

JUNE 17

After Hours (Martin Scorsese, 1985) = 3.5/5

Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) meets a woman at a coffee shop and they agree to a date later that night. While riding a cab on the way to the woman's apartment, Paul's $20 note flies out the window. This is the first of many bizarre occurrences that befall him that night. By the end of the film, you will feel as though you went through everything Paul did. The premise wears thin pretty quickly, but this light Scorsese film has enough laughs to make it worthwhile.

JUNE 18

The Vanishing (George Sluizer, 1988) = 5/5

Rex and Saskia are a young couple vacationing in France. When they stop at a service station, Saskia is abducted. Three years later, Rex begins to receive letters from Saskia's abductor. It's a plot like this that you crave as a fan of thrillers. This is a terrifying film with an unforgettable, sadistic payoff. It's eerily poetic and always immersive. It's the idea that evil could be living next door to you that is most frightening.

This film feels like a sequel to a lost work. The characters feel pre-loved. No matter how hard you try to connect with them, you know it won't be enough because Anderson's love for them will ultimately supersede yours. These characters feel like test subjects in a social experiment. I couldn't cosy up to them. I wanted to, but I just couldn't. I just don't like the microcosmic universe Anderson created here.

JUNE 19

The Virgin Suicides (Sofia Coppola, 1999) = 4/5

An absorbing drama about adolescent secrecy and curiosity, and the things that keep us awake at night. Helped immensely by a great score by Air, and a script that finds the perfect balance between subtle humour and heartfelt truths. Even though the title hints at what will happen, it shocks you nonetheless. It shocks you and it leaves you empty. The film is a good advertisement for why you should let teenagers be teenagers.

JUNE 22

Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957) = 4.5/5

At 88 minutes, Kubrick's anti-war film never languishes. Every scene means something and is riveting to watch. The film takes a moral stance without being preachy. Beautifully shot—especially the scenes of trench warfare. Rarely will you see a greater use of tracking shots.

Me and You and Everyone We Know (Miranda July, 2005) = 5/5

This was my second viewing of July's debut film. When I watched it a few years ago, I immediately knew it was one of the best films I have seen in my life. I must admit it wasn't as fascinating this time around, but only in the way looking at a photograph will never make you feel as joyous as you were in the moment it was taken. It is still a brilliant piece of art, but it's the type of film where the first-time viewing is a near-religious experience. Many will dismiss it as "hipster trash", but they are too attached to their preconceived notions. This really is one of the most humanistic films ever made. You do not dissect it. You experience it. A poetic film that captures the beauty of those moments we share with another human being that mean nothing to anyone else but the two of you.

JUNE 23

Swingers (Doug Liman, 1996) = 3.5/5

There's not a lot to this film in terms of plot, but it's still rather enjoyable. We essentially follow a group of male friends as they attempt to pick up women at bars and clubs. It highlights the differences in mindset between 'alpha' and 'beta' males. As someone who has always been very sensitive and reserved around the opposite sex, Jon Favreau's character really resonated with me. I have never been an alpha male, and I don't think I can be. It's just not in my nature. I digress. Beneath the machismo of the characters lies a charming vulnerability. It's not laugh-out-loud funny, but those chuckles add up.

JUNE 24

Faces (John Cassavetes, 1968) = 3/5

John Cassavetes had a very interesting approach to filmmaking. He prioritised love and human relationships above all other thematic concerns. He didn't care that a lot of people would dislike his films. He knew that making a film that people hated was wiser than making a film that inspired apathy in audiences. It would guarantee that he would be remembered. This was only my second Cassavetes film after Opening Night (which I liked without loving). Sadly, I just couldn't get into Faces. It's easy to admire but so difficult to enjoy. In a film where everyone wants to be heard, the dialogue sounds like static. On the surface, that sounds like a very ignorant assessment, but Cassavetes and cinéma vérité are very new to me. The man knew how to work a camera, though.

JUNE 26

The Silence (Ingmar Bergman, 1963) = 3.5/5

The final film in Bergman's 'Trilogy of Faith', following Through a Glass Darkly (which I haven't seen) and Winter Light (which is one of the best films I have ever seen). Bergman layers on the drama, never allowing the audience to surface for air. Sven Nykvist's cinematography adds to the disquieting atmosphere of the film. The performances by Thulin and Lindblom are outstanding. Despite its strengths, the film is simply not long enough to dissect the neuroses of the two sisters. The dialogue wasn't as piercing as it is in Bergman's other films. I just expected a lot more from this one, but it is still worth a watch.

JUNE 27

The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001) = 3/5

OK, so I gave this a 3 out of 5 which is technically a passing grade, but I think this is a failure of a film. It fails because it tries to be a modern masterpiece when, at its heart, it's your run-of-the-mill oddball family comedy. The main thought running through my mind while watching this was "Why should I care?" I am not a big fan of films that rely upon mythologies to work. The characters seldom seemed like real people. They felt like storybook fabrications, and the narration was just obnoxious and left no mystery in the air. I usually love films about dysfunctional families, but only when the dysfunction organically evolves out of seemingly innocuous situations. In this film, Anderson was so desperate to let us know how fucked up everyone was. We already know this family is dysfunctional and eccentric after the opening scenes. It's lazy characterisation.

This film feels like a sequel to a lost work. The characters feel pre-loved. No matter how hard you try to connect with them, you know it won't be enough because Anderson's love for them will ultimately supersede yours. These characters feel like test subjects in a social experiment. I couldn't cosy up to them. I wanted to, but I just couldn't. I just don't like the microcosmic universe Anderson created here.

Oh, and for a film that claims to be a comedy, I barely chuckled.

Another major flaw of this film is that it lacks an emotional centre. Anderson jumps from character to character and from story arc to story arc before we can establish any meaningful connection with the characters. Shots are overstuffed with visual stimuli. I didn't know what to look at, and I cringed at how artsy Anderson was trying to be in a film that didn't warrant excessive artsiness. Nothing emotionally affected me. There are scenes here that may have made me cry if they were in a more measured, cohesive film.

So, what's good about this film? The cinematography, the soundtrack, and the performances (not outstanding, but good considering the material). It seems like I've bashed this film quite a bit, so I think it did pretty well to earn a 3.

Another major flaw of this film is that it lacks an emotional centre. Anderson jumps from character to character and from story arc to story arc before we can establish any meaningful connection with the characters. Shots are overstuffed with visual stimuli. I didn't know what to look at, and I cringed at how artsy Anderson was trying to be in a film that didn't warrant excessive artsiness. Nothing emotionally affected me. There are scenes here that may have made me cry if they were in a more measured, cohesive film.

So, what's good about this film? The cinematography, the soundtrack, and the performances (not outstanding, but good considering the material). It seems like I've bashed this film quite a bit, so I think it did pretty well to earn a 3.

JUNE 28

Despicable Me (Pierre Coffin & Chris Renaud, 2010) = 4.5/5

There are few things more gratifying as a film enthusiast than watching a film you don't expect much from and being absolutely blown away. I was at a friend's house for a movie night and this was the movie we decided on. I couldn't believe how engrossed I was. The cliches are easy to disregard because the characters are so engaging. It had me laughing a lot, and I can't remember the last time a film filled me with this much joy. Oh, and please, DO NOT compare this film with something from Pixar. Everyone knows the brilliance that Pixar is capable of, but I think this film is just as good as something they would do (and better than some films they've already done). I get the feeling people will be snobbish and say "Meh. Not from Pixar; don't care." Do not make that mistake.

JUNE 30

I Stand Alone (Gaspar Noé, 1998) = 4/5

This is an almost nihilistic work that makes you question the arbitrariness of everyday life. The Butcher (Philippe Nahon) has lived an unsatisfactory life, full of misery and regret. For him, "surviving is a genetic law," not something he does because he enjoys it. There is a monologue in this film that gave me chills. The Butcher delivers it after he witnesses an elderly woman die. It contains no niceties or comforting remarks. In essence, it argues that we do not truly love our family or friends. The feelings we have for them are the product of necessity, to propel our own existences. I didn't necessarily agree with what was being said, but there was enough truth to the words to make me uncomfortable. A confronting and unforgettable film that will stay with you for days.

In Summary - The Must-See Films (4.5 or 5 Stars)

* The Black Balloon

* The Red Shoes

* The Vanishing

* Paths of Glory

* Me and You and Everyone We Know

* Despicable Me

_01.jpg)